Skilled workers for international companies

There is an urgent need for skilled workers in Japan. Why two companies are now implementing Germany’s dual vocational training model for the first time.

Koko Mori is 19 years old and loves fast cars. The young man from near Osaka is happiest when he can spend his weekends underneath his car, inspecting the control arm, undercarriage, brake pads and other wear parts. Six months ago he turned his passion into a career - he now works for the Daimler truck subsidiary Mitsubishi Fuso.

His instructor there told him about a concept that hasn’t existed in Japan until now: dual vocational training based on the German model, involving a combination of practical training at a company and theoretical instruction at a vocational school. On 1 April 2024, Koko Mori and 20 others began a three-year training programme to become car mechanics. “I wanted to know more and learn more so that I can enjoy my work even more,” explains Koko Mori, who has so far been working in the vehicle inspection department and changing tyres. Now he will learn everything about how a vehicle works and how to identify faults - and ideally how to remedy them. “Perhaps I’ll also be able to use this knowledge on my own car,” he says with a laugh. Previously he had never heard of this concept of dual vocational training. “But now I’m excited to see what it will involve and am really looking forward to it.”

It is not without good reason that the companies BMW Japan and Mitsubishi Fuso are now also introducing the dual vocational training model in Japan: Just like Germany, Japan is facing the challenges posed by a skilled labour shortage. With a super-aged society, the country desperately needs specialists, especially in the automotive industry and in international companies.

In a survey conducted by the German Chamber of Commerce Abroad, more than 80 percent of German companies operating in Japan said that they were having problems recruiting qualified personnel. The dual vocational training model could help remedy this situation. Until now, young people in Japan would either learn the theoretical knowledge they need for their profession at an academy, or they would learn the practical skills of their trade in five years of training at a company. Dual vocational training shortens this period by two years and combines general specialist knowledge with the specific knowledge needed at the company in question. As is also the norm in Germany, Koko Mori is paid a salary right from day one of his training. He spends four days a week working and learning at the company, and once a week takes a roughly two-hour journey by train to the vocational school in Kobe, where he learns the basic principles of vehicle mechatronics. Once he has completed his training, he can begin working at the company full-time.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

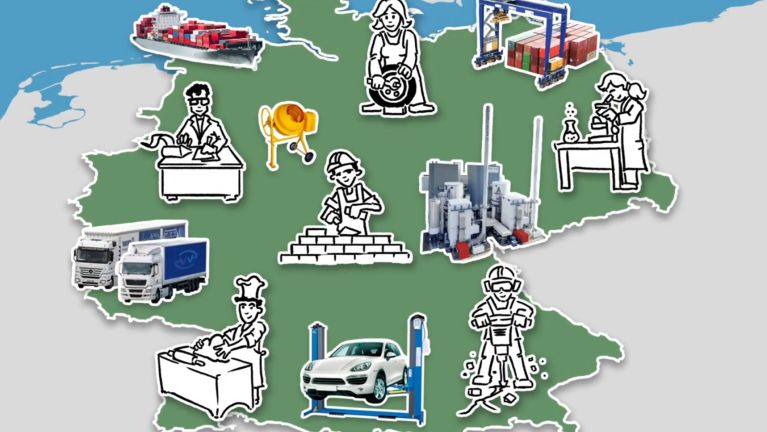

Open consent formGermany’s vocational training model has become a successful export. The concept has already been introduced in 48 countries, with more than 27,000 young people outside Germany having already completed training based on the German model. In Vietnam, for example, young people can embark on a training programme in industrial mechanics, architectural drawing or the catering sector. In the Philippines, training is available in mechatronic repair or the cleaning industry. In India, vocational training is on offer for welders, tool mechanics and mechatronic engineers, for example. Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Thailand are also using the German model to train their young people. Further collaborations are in the pipeline. Germany is collaborating with more than 100 countries that are interested in its vocational training concept.

South Korea has served as the role model for Japan’s further development of the concept. Lucas Witoslawski, who runs the project at the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Japan, explains that three companies initially implemented the dual vocational training model in South Korea in 2017 and that this number has now grown to seven. In South Korea, where leading German companies such as Daimler, Audi and MAN are now using the model to train their apprentices, the dual vocational training system is countering not only the skilled labour shortage but also the high rate of youth unemployment. Those involved in the project also hope that Japan will show a similarly rapid development. The goal is to have 50 trainees per year by 2025 and 100 in each subsequent year. For this to happen, however, more companies and vocational schools will need to be recruited to the programme.

For Sora Kodama, who has likewise been an apprentice at Mitsubishi Fuso since April 2024, the dual vocational training programme is above all an opportunity to advance his career at the company. “Previously, I had to learn all the theory on top of my regular work - now I can learn the basic theoretical principles again that will later enable me to take on more responsible roles,” he says. As Kodama has already worked at the company for five years, he is hoping to qualify as a “master tradesman”. Rather than working in the vehicle inspection department as he does now, he wants to concentrate more on vehicle maintenance once he has completed his training. Another thing is also important to the 25-year-old, however: “I am making my family happy,” he explains. “My parents were already pleased when I joined the company. But now they are really proud.”