Art in exile

The Goethe-Institut is supporting artists from countries where it is no longer able to work. Ukrainian art is the first step.

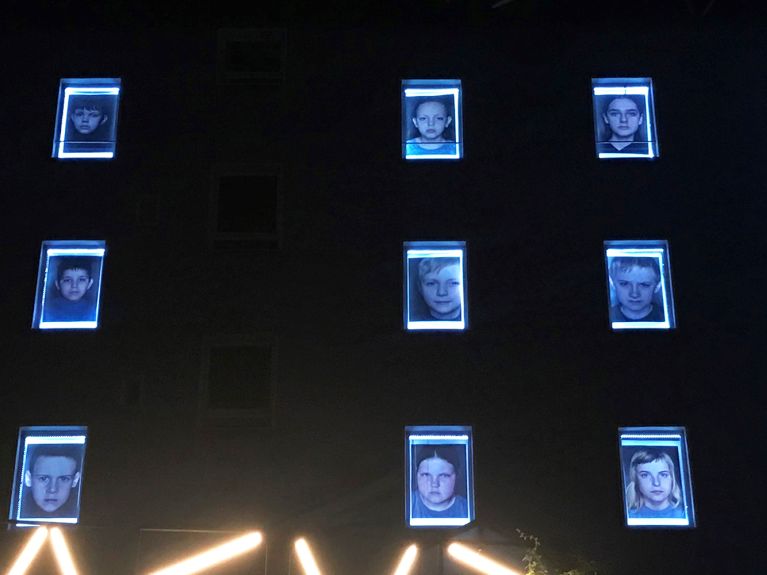

Children’s faces can be seen at the windows of the ACUD cultural centre in Berlin – portraits taken last year in Donbass by the Ukrainian photographer Helen Bozhko. “These are the faces of children who are suffering from the war. A war that was already raging in eastern Ukraine before 24 February,” explains Olga Sievers. She is curator and project manager of the “Goethe-Institut in Exile” in Berlin. Each face tells its own story. Nobody knows what has become of the children since their photographs were taken. However, Ukrainian artists are keen to show that there are these stories from Ukraine.

The two-year “Goethe-Institut in Exile” project was launched during an opening festival at ACUD in early October 2022. Ukrainian artists came together to exhibit their art during their exile in Berlin. The next six months are to be devoted to this country that is under attack from Russia. Sievers’ Ukrainian colleagues are continuing their work in digital form despite the Goethe-Institut in Kyiv having closed, Berlin having become their “event outpost”. A similar festival for Afghan artists is planned in the spring. This will be followed by events staged by the other Goethe-Institut branches that have been closed due to war or censorship in Syria and Belarus.

Creating connections

Anyone wishing to continue their art in exile needs to be connected – to structures, institutions and other artists. Berlin’s Goethe-Institut thus wants to serve as a point of contact and safe space until the institutes in the four countries can reopen. Olga Sievers does not in any way dictate the form that events should take: “We listen to the artists and see what we can make happen together.”

After all, the four countries differ considerably. Art in Ukraine can still be freely pursued, yet the work of the Goethe-Institut is no longer safe. In addition to the many artists who have fled the country or have already been living in exile for some time, many more undertook the arduous journey from Ukraine to attend the opening festival. It takes over 24 hours to reach Berlin, no matter which route one takes. By contrast, only exiled artists from Afghanistan, Syria and Belarus are expected to attend, or online events will be held, in some cases featuring anonymous works.

A slice of home

It was already clear during the opening festival how eager the artists are to engage in exchange with one another. Viktoria Leléka, a singer with the jazz and folklore group “Leléka”, has been living in Berlin for several years. She was at ACUD every day. “Many people found it overwhelming to see so much of their own culture,” recounts Olga Sievers. She tells of refugee children who came to a workshop given by the illustrator Lana Ra and began painting immediately: “You could see from their faces that this was like having a slice of home here in Berlin.” And when Serhij Zhadan took to the stage with his band, the place was packed, the audience spilling out into the courtyard. Apparently it was amazing how many of them knew the words to the songs.

The Ukrainian voice

Apart from offering space for exhibitions, installations and films, ACUD is also home to a club. “Bomb Shelter Night”, a performance given there by the groups DACH and Gogol-Fest, lasted seven hours. The concert was interrupted by air-raid sirens to simulate a night of partying in Kyiv. While the audience sought shelter, diary entries from the start of the war were read aloud in various languages. This gave non-Ukrainian audience members the chance to get a sense of this unimaginable situation. “The conversations prompted a lot of tears,” says Olga Sievers, adding that an awareness team was on hand to ensure that nobody was left alone with their feelings.

“An author can give a much more impactful account of what life is really like in Kharkiv than a news report can,” says Evgenia Lopata. With her publishing house Meridian Czernowitz, she organises an important part of the festival. Because she is responsible for the publisher’s literary programme, she travelled to Berlin with authors from Ukraine: Iryna Tsilyk, Andriy Lyubka and Roman Malinovskiy, who regularly help out on the front line, giving a voice to the war in their lyrics. As the mouthpiece of Ukrainian literature, Lopata wants to make the texts as well-known as possible “so that European also view us as citizens, as a country in its own right”.

Breaking with old narratives

This is because there is another matter – besides networking – that is close to the artists‘ hearts: they are determined to show that Ukrainian culture already existed before the Soviet Union. “My parents have lived their whole lives in Chernivtsi but had not heard of Paul Celan until 2010,” explains Lopata. “We were unaware of the foundation of our lives.” Until Ukraine became independent in 1991, she says, so much that had been established in multicultural cities like Chernivtsi had been suppressed. Lopata also views the “Goethe-Institut in Exile” as an opportunity to talk about the cultural legacy of Ukraine. She admits that the festival and subsequent reading tour completely exhausted her, but that she felt honoured by the communication and empathy that was shown.

Olga Sievers explains that the others experienced much the same as Lopata: “Not one of the people we asked said they wouldn’t do it”. When Russia attacked Kyiv and other cities with bombs and missiles on 10 October, most of the artists were due to travel back home. Sievers believes that from a German perspective it is virtually impossible to comprehend what they must have been feeling at that time. However, it was quite clear that now in particular they really wanted to go back. She describes it as an incredible balancing act: “It was so important for them to reach out to audiences here, yet at the same time their hearts beat for Ukraine.”