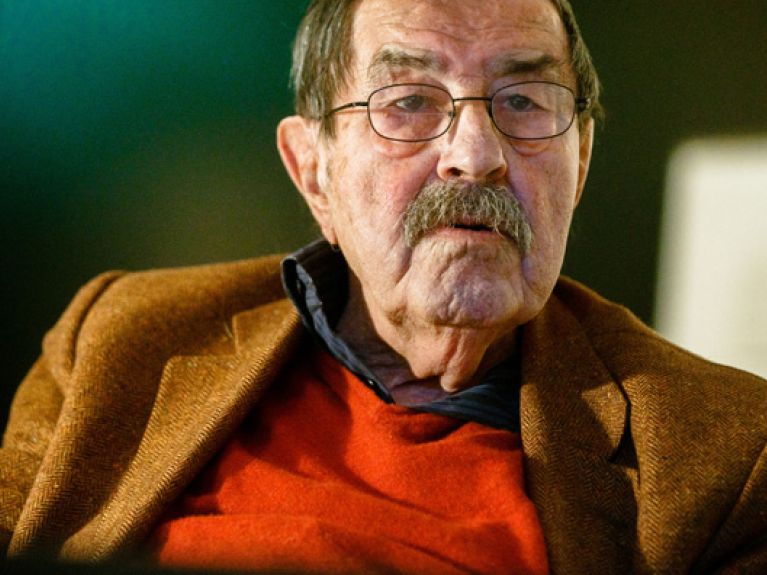

Guenter Grass dead

Widely acknowledged as a towering giant of German literature, Guenter Grass dies at the age of 87.

For some, Guenter Grass is a towering literary figure, a magnificent storyteller, who in the words of the Swedish Academy's Nobel Prize committee "has done mankind a genuine service." For others, he is a self-appointed moralist for postwar Germany, a righteous polemicist who attacked his fellow countrymen for their collective amnesia of Nazism while at the same time failing to own up to his own lapses in recalling the past.

Grass, who died Monday from an infection at the age of 87, is arguably one of Europe's greatest living writers with over half a century of literary success and political commitment.

Born in 1927 of German-Polish parents in Danzig, now Gdansk, in Poland, he was the last Nobel literature laureate of the 20th century. "For me, Guenter Grass is one of the greatest writers of our times, whose inflexibility, courage and emancipatory conviction I admire greatly," former chancellor Gerhard Schroeder said at the time of his 80th birthday.

His international breakthrough came in 1959 with The Tin Drum, an allegorical novel set in his home town, that was turned into a successful film by director Volker Schloendorff. When he published The Tin Drum, "it was as if German literature had been granted a new beginning after decades of linguistic and moral destruction," the Swedish Academy wrote.

Other works followed, including Cat and Mouse, Dog Days, From the Diary of a Snail, The Flounder and The Rat. "Grass' novels strip their characters of grand words and emphasize the solidity of the flesh by bringing human forms close to the animal world. We all have a place in his menagerie," Horace Engdahl said in his presentation speech at the Nobel award ceremony in 1999.

A left-winger and a pacifist, Grass became active in politics in the 1960s and took part in election campaigns on behalf of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and its leader at the time, Willy Brandt. He advocated a Germany free from fanaticism and totalitarian ideologies in his political speeches and essays and used The Flounder and The Rat to reflect on his commitment to the peace and environmental movements.

Not all his works were well received, however. Marcel Reich-Ranicki, one of Germany's foremost literary critics, spoke of "books of vastly differing quality."

But it was his 2006 novel Peeling the Onion that aroused the most controversy. The book, spanning 20 years of the author's youth, included the shock admission that he was briefly a member of Hitler's elite squadron, the Waffen-SS, during the latter part of World War II. The disclosure rocked Grass' reputation as a moral authority, and some of his adversaries even claimed the revelation was no more than an exercise in damage control before others exposed the truth.

In 1944 he was wounded and captured by US forces who kept him as a prisoner of war. After his release he became a labourer, then an artist, living in Paris before settling in Berlin. Grass described himself as "a belated apostle of enlightenment" in an era that has grown tired of reason. In his excavation of the past, he goes deeper than most.

This was vividly demonstrated in his 2002 novel Crabwalk, in which Grass deals with the fate of the Wilhelm Gustloff, a German ship packed with refugees that was hit by a Soviet torpedo in the Baltic Sea and sank with the loss of 9,000 lives in January 1945. Moving crab-like back and forth among facts about the disaster, the lives of the characters in the events leading up to it, and the saga of the book's narrator and his family, Grass analyzes Germany's past and present, while hinting darkly at its future.

This future was looking increasingly regimented in view of recent calls by authorities for surveillance of citizens' emails to combat terrorism, he said at the time in an interview with Deutsche Presse-Agentur dpa. "At the moment we are about to dismantle (democracy). A hysterical fear of terrorism is turning us more and more into a nation of surveillance," he said.

Grass lived with his second wife Ute near the north German port of Luebeck, where a small museum called the Guenter Grass House contains the original manuscripts of some of his works.

(dpa)