Faces and stories

Their creativity and commitment are making Germany a richer place: four men and women with African roots, who live and work in Germany

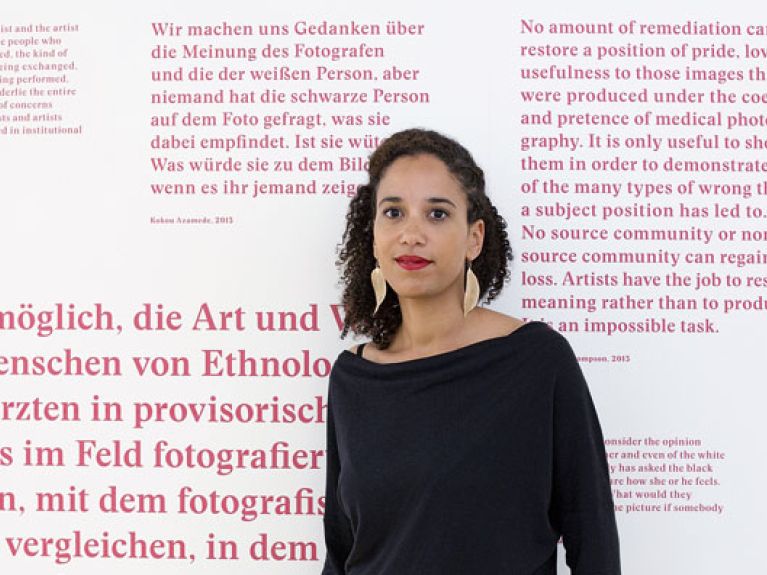

Yvette Mutumba

Lots of the things she says are a bombshell. “There is no African art” is one of them. Yvette Mutumba has a doctorate in art history and has been engaged in educational work for several years now. The concern most important to her is to show people from Western cultures that Africa can look back on a diverse, complex history of art. Unlike what many people perhaps think, this history of art refers not to traditional wood sculptures, but for example to contemporary art, she says. Mutumba spent pivotal moments of her early childhood in the Congo and later studied history of art at the Free University in Berlin. Today she works as a research curator for Africa at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main. And she helps give a new presence to works by contemporary artists with links to Africa. In 2013 she founded Contemporary And (C&). The online platform provides an extensive view of art production in Africa. With her work she is playing an important role in heightening the West’s perception of African art. ▪

Clara Krug

Amadou Diallo

His grandmother and Che Guevara – these are the two people that come to mind when Amadou Diallo is asked who his role models are. Then he laughs a little before saying that of course he doesn’t have the same aims as the Marxist revolutionary from Latin America, though he has always been impressed by the latter’s energy and fighting spirit. Diallo’s grandmother, Aissatou Labé, is far more important; he spent a large part of his childhood and youth at her home. Born in Senegal, he grew up in Dakar with nine siblings and his parents. Yet from when he was ten years old he always spent the summer in his grandmother’s village in the Kolda region in the southwest of the country. She was the midwife for the women in the village and an arbitrator everyone accepted whenever there were disputes.

“My Granny,” Amadou Diallo says – and there is almost a Rhineland lilt in the way he says “Granny”, which could be due to the fact that Amadou Diallo has been living in Bonn for several years now – “my Granny taught me that if you work hard and are prepared to make sacrifices for your goals, something good will always come of it.” And that is something he has never forgotten. Diallo fought for his aims and his dreams. The son of a shoe seller, he managed to study economics in Germany, France, and the USA. He speaks six languages fluently and has worked for the German logistics company DHL, first in Marseille, and later in Singapore. Since 2011 the 52-year old has been CEO of DHL Freight, and as such responsible for its international road and rail freight forwarding business, which has annual sales in excess of four billion euros. And he is responsible for Africa: the company operates in all African countries and its employees there come predominantly from that continent. He wishes for more investment in Africa, wants opportunities in particular for the continent’s young people, hopes there will be more jobs for them, more awareness in Europe of their skills and drive. “I’m no exception,” he believes, “there are lots of people in Africa like myself.” Of course you need ambition and talent, he adds. “But also people who believe in you and support you.”

Biographies such as his are still rare. In German companies there are few men and women from Africa in top management positions. “That sometimes results in people having inhibitions in their dealings with me,” Amadou Diallo observes, “simply because it’s a situation they are unfamiliar with.” He hopes that executives in particular avail themselves of the opportunity to get to know Africa and its people through travel. There is basically an optimistic, cheerful attitude to life there, he says. He likes the German work ethic. Diallo has no wish to, indeed is unable to not put his time to good use.

In addition to his work, Diallo is a volunteer for several NGOs – for Amref Health Germany, for example, and for the Global Business School Network. Diallo dreams that one day an entire generation of girls and women in Senegal will receive a school education. In 2011 the business magazine Africa Investor bestowed its Africa‘s Innovation Leader award on him for his commitment. Diallo emphasises that he has received a lot of help along the way. Diallo is convinced that “at the end of the day it’s not having millions in the bank that counts, but rather that our children and grandchildren can live in a better, safer world.” ▪

Natascha Gillenberg

Ntagahoraho Burihabwa

His name means “everything changes” in Kirundi. For Ntagahoraho Burihabwa, that could well be the motto of his life. He has refuted prejudices and clichés, adopted various roles, and lived in different worlds. He himself has experienced what discrimination means – and how you can defend yourself against it. But nevertheless there is one thing that hasn’t changed: Burihabwa likes being a German.

That said, he began life as a stateless person. Burihabwa was born in 1981 in Siegen in North Rhine-Westphalia, to parents who come from Burundi. For the Burihabwas there was no way back to their crisis-ridden home country, since they had been stripped of their Burundian citizenship. The father worked as an engineer in Siegen. Only later were the Burihabwas given German passports. By then they had already left Germany. Ntagahoraho grew up in Kenya. In Nairobi, Gaho, as he is known to his friends, attended the German School. “Even then I felt like a German, and was proud of it,“ Burihabwa recalls. Only when the family revisited Germany in the early 1990s did he notice that he was different from most other Germans. At the time the xenophobic attacks in Mölln, Solingen, and Rostock’s Lichtenhagen district were keeping the recently reunited republic on tenterhooks. Burihabwa himself also experienced hostility, was staggered by it.

But he wasn’t discouraged. After completing his Abitur exams, he volunteered for the Bundeswehr, the German armed forces. Lots of his acquaintances advised him against doing so, but Burihabwa didn’t listen to them. At the beginning of September 2000 he enlisted for military service in Montabaur in Rhineland-Palatinate. Burihabwa was initially suspicious, and in the barracks chose the bed from which he thought he could best keep the six-man room under observation.

He hardly experienced any discrimination due to the colour of his skin, however, and felt at ease in the Bundeswehr. He studied education and history, graduated with top marks and later became a group leader at the Bundeswehr’s university in Hamburg. But he is annoyed by the way integration is talked about in Germany. In 2010 the economist Thilo Sarrazin made the headlines with his claim that the majority of migrants in Germany were uneducated and unemployed. In response to Sarrazin’s populist theories Burihabwa founded an association by the name of Deutscher Soldat e.V. for soldiers with immigrant backgrounds. Among other things, its 120 members are working to ensure that anybody who feels German should be regarded as such. Burihabwa has since left the Bundeswehr, but is still a reserve officer. In his new job he also deals with questions relating to war and peace. In 2015 he began working in the Department for Peacekeeping Operations at the United Nations in New York. ▪

Julia Egleder

Musa Bala Darboe

When Musa Bala Darboe arrived in Germany in 2010 he didn’t waste a second thinking about staying for any length of time. A mere youth, he had fled from his home country Gambia on his own because he had championed human rights there and was persecuted as a result. He missed his family and friends. And in everyday life he had found making himself understood difficult because English often didn’t get him very far. “I had to start from scratch again,” Darboe recalls. “For this reason I initially thought this country is not for me.”

He is of a different opinion nowadays: “I see my prospects here in Germany.” On the one hand that is because of the support he received – for example, from the staff at the youth welfare office in Düsseldorf, at the Psychosocial Centre in Düsseldorf, and at the Hans Böckler Foundation. And on the other because he worked hard. He learned German in just a few months, and just a few months later went to secondary school. Only three years after arriving in Germany he had passed the university entrance exam for specific subjects. Following a one-year internship at GLS Bank’s foundation Zukunftsstiftung Entwicklung he is now studying business administration and specialising in computer science.

Darboe is a person who is in charge of his own life, and so it is hardly surprising to discover that when he graduates he would like to be self-employed. Even now he is in contact with other start-up founders, finding out what is important when you set up your own business.

The basic idea behind his future company is for other people to be able to utilise their skills as well as possible. His credo is fair working conditions rather than maximum profit. Darboe’s voluntary work for the youth organisation Jugendliche ohne Grenzen also focuses on promoting people’s potential. He has been working voluntarily for this national association of young refugees since 2014. “We want to give refugees a voice of their own, which they can make heard in discussions that affect them.” For this reason he and his fellow campaigners attend events dedicated to topics such as migration, asylum and flight. By way of example, at a recent event Darboe discussed health service cards for refugees with other participants.

Jugendliche ohne Grenzen also organises German language courses to make it easier for refugees to take part in life in Germany. And it arranges neighbourhood meetings with recipes and dishes from refugees’ home countries to build bridges between them and other people in Germany. “In the process we also aim to overcome prejudices and make it clear to people that, just like them, we want to work, pay taxes and shape society.” With his commitment and ideas Musa Bala Darboe is demonstrating what form that can take. ▪

Hendrik Bensch