The Children of Karl Marx and Coca Cola

The myth of “1968”: many interpretations lead astray. What the 68ers really wanted and what distinguishes them from today’s protest movements.

A guest commentary by Heinz Bude, originally published in the Frankfurt Magazine of the Frankfurt Book Fair.

When we think of 1968 we think of the sit-ins and go-ins, of the Rolling Stones’ ‘I can’t get no’, of the raised and black-golved fists of the American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the winners’ podium in the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico, of ‘Why don’t we do it in the road?’, of the American national anthem distorted by Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock, the protests against the Vietnam War and of course Karl Marx. Not least of Bob Dylan, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature last year, and didn’t appear for the award ceremony, and Ulrike Meinhof as painted by Gerhard Richter in his Stammheim cycle.

Today, 68 is seen from a liberal, cosmopolitan-minded class as the start of a fundamental liberalisation process in western societies, and by right-wing populists as the beginning of the decline of the western world, which can no longer summon the strength to resist settlers from all the countries in the world.

1968: The last hot revolution and the first cool revolt

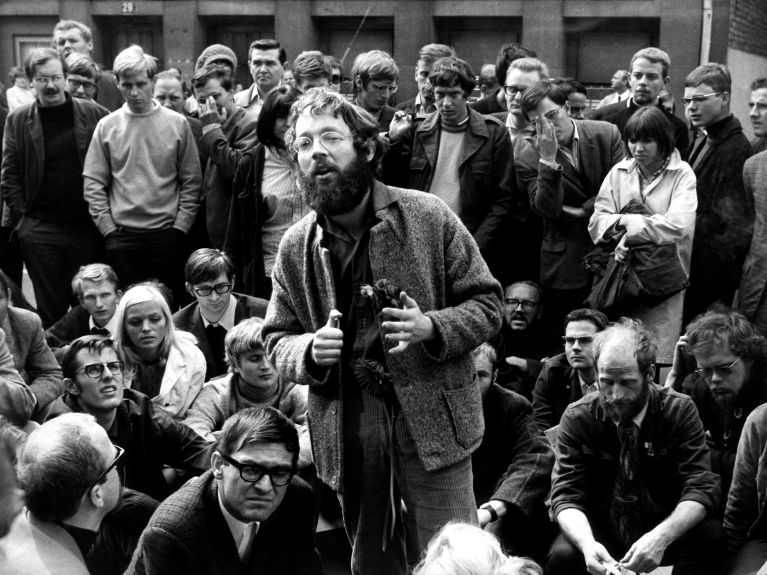

But what was 68 really? The French historian Paul Veyne, to whom we owe a big book about the republican pleasures of the ancient Romans entitled Bread and Circuses, once described 68 as the last hot revolution and the first cool revolt. For the last time the whole revolutionary register was presented with readings of Das Kapital, distinctions between friends and enemies in the class struggle and world-historical end games according to the motto ‘Socialism or Barbarism’. But the revolutionarily-minded awakening came to public attention by slyly playing with ever-new deliberate violations of the rules. ‘If it serves to help establish the truth’, was the answer given by the defendant Fritz Teufel when a judge ordered him to rise before the court. It wasn’t the size of the crowds – demonstrations with 10,000 or 15,000 participants were simply too small for that – but a thousand tiny provocations that the revolt broke new ground and dominated the media. The whole world was watching.

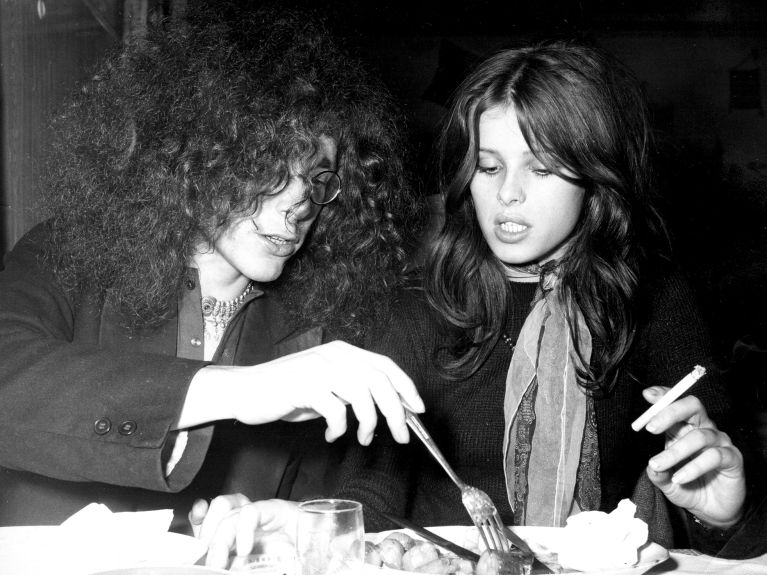

So the ignition of 1968 consisted in a mixture of a desperately serious desire to improve the world, and a cheerful disarrangement of the world. Jean-Luc Godard, who said he made his films not when shooting, but when eating, drinking, reading and dreaming, called the actors, with wicked precision, ‘The children of Karl Marx and Coca Cola’. The actions, particularly the actions of students, were aimed at the clean divisions of bourgeois life, where work, love, politics, art, pleasure and science could communicate but not intermingle. In post-war societies, which still had World War II and genocide in their bones, there was a powerful anxiety that the whole thing might otherwise come crashing down.

The soundtrack consisting of philosophy, rock, cinema and happenings

But the 68-ers, born between 1938 and 1948 couldn’t have given a damn about any of that. And in any case, as Theodor Adorno insisted, it was the inauthentic in any case. People heard the big words of this small man with the child’s eyes and knew, even though they didn’t fully understand the full import, that they were the right words. A rebellious experience was one which delivered itself up to a negative, endless dialectic which never led to the final sublation. It is part of the passion of 1968 that philosophy, rock, cinema and happening created a sound from which no one who felt young could exclude themselves. The movement thus became the movement by simply crossing boundaries which a generation before had been the conditions on the possibility of civility freedom and affluence.

But the interpretation of 1968 was disputed from the outset. Thus, for example, Jürgen Habermas and Karl Heinz Bohrer at the time put forward competing interpretations of the events playing out in front of their eyes. One as a radical democrat, the other as an absolute aesthete. What Habermas saw as models of civil disobedience, Bohrer dismissed as the self-justifications of a new left-wing ‘juste milieu’. While Bohrer saw the return of Surrealism in the best parts of 1969, Habermas drew the boundary between unprincipled activists for whom ‘direct action’ was more important than ‘dominance-free discourse’, and the bulk of those who were mostly fed up with the ‘mildew of a thousand years’ at the universities. One of them drew a long line that extends from 1968 to Barack Obama and Angela Merkel, the other insists even today on the madness of an interruption that cannot be claimed for any idea. Both referred to the inspiration of Walter Benjamin, who famously considered it a disaster that everything continued on its course.

1968 consisted in the discovery of society as a category for the understanding of the personal practice of life. For subsequent generations, who make jokes about floating signifiers such as ‘socialisation’, ‘communication’ and ‘interaction’, that is hard to understand. One needs to consult novels like Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates or television series like Mad Men to understand how the revolution, influenced by Marx and Freud, Herbert Marcuse and Louis Althusser, R.D. Laing and Shulamith Firestone, emerged from a post-war world peopled by isolated existences in an atmosphere based on the communicative silencing of Stalingrad and Auschwitz.

The concept of society was much more than an instrument for the sociological explanation of the world; it contained the promise that the self-doubting ego might overcome itself. There was a connection between personal unhappiness and social injustice. For that reason the laments of the self could become a legitimate object of political demands. Not only sociology, but also linguistics, psychoanalysis and social history or social psychiatry constituted a new kind of knowledge that combined precise description with normative demands. This new knowledge of 68, as French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu put it, promised a lot but demanded little.

1968 wasn’t the start of anything that hadn’t existed before.

For contemporaries, 1968 came out of the blue. In spite of Jefferson Airplane, who first performed in 1965, in spite of the critique of empty lives in the suburbs, in spite of the feeling of a latent depression, the revolt of a younger generation was clearly unexpected. But when this movement of underground art, campus revolts and revolutionary circles suddenly existed, a rigid society was freed to become itself. People were actually waiting for something different to come, but couldn’t imagine what it might be.

"Sleep with the same girl twice, you’re part of the establishment"

For that reason all evolutionary interpretations of 68 are misleading. It wasn’t the start of anything that hadn’t existed before. Either the sexual revolution or the democratisation of society, and above all not the confrontation with Auschwitz. The Kinsey Report was much earlier, the theory of Social Democracy was already being dealt with in Europe by the Social Democratic parties, the Eichmann trial had been held in Jerusalem. The search for the social and historical tendency expressed in 1968 only conceals the mixture of melancholy and longing, radical reflection and rebellious energy, political Dadaism and attempts at existential rebellion which were typical of the breach opened by that year. Did the generation of 1968 believe in their myths? When they chanted in the street ‘Wer zweimal mit derselben pennt, gehört schon zum Establishment‘ (‘Sleep with the same girl twice, you’re part of the establishment’), indeed if they went home at night as scrawny figures in their bellbottoms and fringed jackets, no. The paradox is that today’s culturally militant right wing is accusing 1968 of doing something that it seeks to do itself: making history by setting a supposed apocalypse off against another one, to create a new order from this chaos.

But today’s young left is also trying to find connections with 1968. For a moment it actually looked as if Occupy Wall Street, the Indignados in Spain or Syriza in Greece represented a new 68. The 68-ers were concerned about liberation, and the anti-racist, post-colonial, no longer imperial left of today is concerned with justice. The call for justice seeks to extend and deepen rights, while the desire for liberation wants to shake everything up. The legacy of 68 consists in amazement that fifty years ago, for a brief moment and as the result of a crazy impulse, that succeeded.

Between 1997 and 2015 Heinz Bude ran the ‘Society in the Federal Republic’ section at the Hamburg Insitute for Social Research. Since 2000 he has held the chair of Macrosociology at the University of Kassel. In January 2018 he published Adorno für Ruinenkinder. Eine Geschichte von 1968 (Adorno for Children of the Ruins. A History of 1968).