Houses that stand out

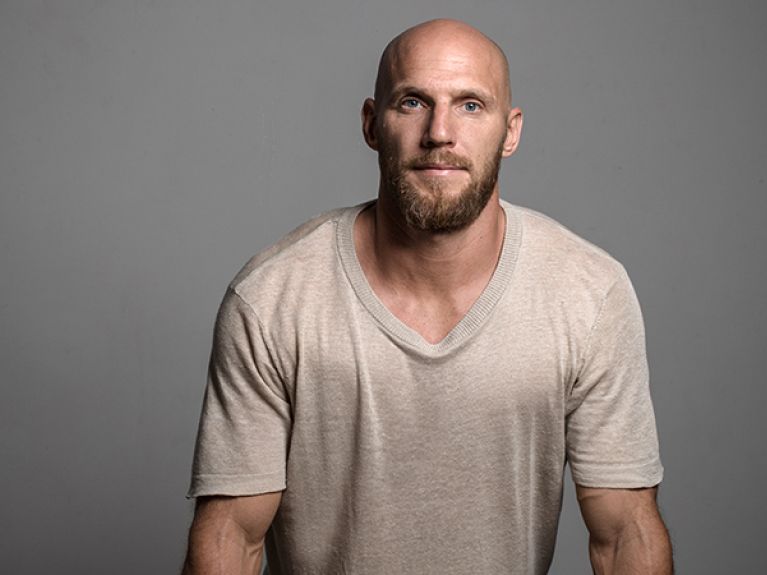

Why Alexis Dornier, the great-grandson of a German aircraft designer, designs houses in Bali.

Actually, Alexis Dornier only wanted to relax for a summer in Bali; just leave Berlin and his design company behind and do nothing. That was in 2013. Today around 20 buildings designed by the 39-year-old German architect stand on the Indonesian island in the Indian Ocean. And Dornier now employs a team of 25 designers from Indonesia, Germany and India.

It all started with a house for a friend who invited Dornier to Bali. This is located in a settlement of artists and entrepreneurs from all over the world. Dornier liked the “lifestyle of the expat community” straightaway. He was amazed that so many interesting people were gathered on such a small island. The friend’s neighbour also wanted a Dornier house, and eventually the architect designed eight villas for the settlement.

Dornier emphasizes that he isn’t someone who wanted to leave Germany behind. On the contrary, “I like our western culture”, he says. Nor did he break camp in Germany right away. But young architects in Germany rarely have the chance to design dream houses, he says. After studying architecture at the University of the Arts in Berlin, Dornier founded his own design company. He designed interiors for bars and discos and ran an art gallery on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz. Sometimes he was commissioned for the exhibition stand of a fashion designer, sometimes for the design of loudspeakers. But he didn't really get a chance as an architect.

Between industrial architecture and tropical modernism

Bali taught him not to take himself so seriously and gave him the courage to try new things. Today Dornier’s style can be described as a mix of industrial architecture and tropical modernism, with elements from traditional Indonesian architecture. He already drew the attention of international architecture magazines with his Origami House, s so called because of its folded tent roof.

To make relevant contributions to the discussion in international architecture.

Kohlhaas’s famous architecture firm OMA in New York from 2003 to 2006 also shaped Dornier’s style. Just as Kohlhaas interweaves the urban environment like a collage into his designs, Dornier does the same with nature.

Houses in dialogue with nature

Dornier’s houses blend in perfectly with rice fields and tropical wilderness in terms of colour and design. But they don’t disappear into the environment; on the contrary, a subtle interplay between built elements and plants unfolds all around. It seems as if the houses are entering into a dialogue with nature. Steel girders, concrete walls, wide, often curved roof overhangs and lots of wood are characteristic of Dornier’s buildings. Colours are used only to a very limited extent: plants, turquoise pool water and wooden furniture with green cushions between grey concrete and dark steel. The open architecture with flowing transitions from inside to outside is tailored to the tropical climate.

It seems that Dornier was born with a wide range of artistic interests, coupled with technical talent. His great-grandfather was the famous aircraft designer Claude Dornier. Flying is still very dominant in the family, but never became his passion, says Dornier. On his mother’s side of the family, on the other hand, art is very important. This doubtless led Dornier not to limit himself to architecture alone. He is co-owner of three restaurants in Bali and markets a skin care range with his partner.

His favourite project at present is Stilt Studios. In 2019, he founded a company with a customer to build and market stilt houses. They were to be minimalist and as sustainable as possible. The rooms float on steel supports as in a tree house. Because the environment is intervened with only selectively, the houses can be set up in the middle of nature and make use of their surroundings: the wind at lofty heights and trees as shade donors to avoid air conditioning. Anyone interested can buy the blueprints and build their own stilt house anywhere in the world. Stilt Studios are already at eight locations in Indonesia and have received orders from India and the Caribbean.

A completely different project is the design of a school house for girls who have experienced sexual violence. Suddenly, Dornier faced a whole new set of new requirements. Now not the number of bathrooms has to be discussed but rather: How can architecture provide support? For Dornier, this is a challenge he is happy to accept. “My long-term goal is to make more relevant contributions to the discussion in international architecture”, he says. Public buildings instead of private villas, also in Europe.