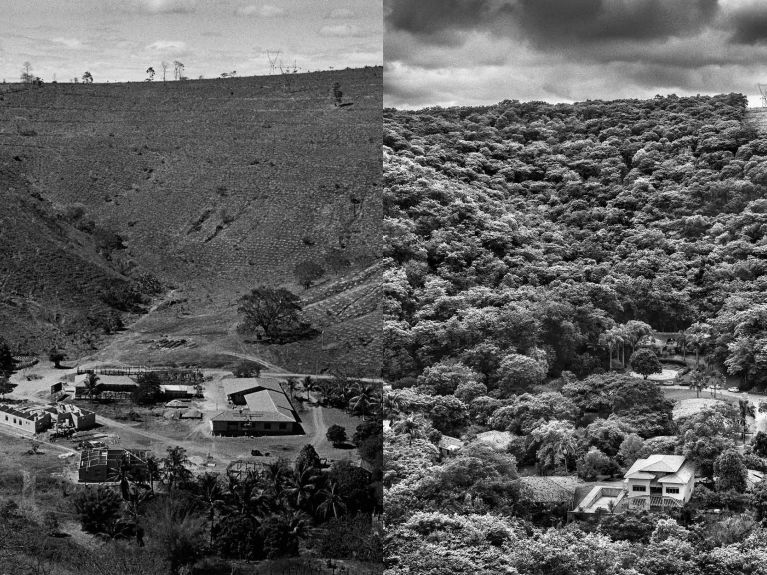

“Planting trees to be able to live in peace“

Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado transformed his parents’ farm into a nature reserve. It is maintained with German support.

Sebastião Salgado is a Brazilian photographer known for his impressive black and white photographs documenting social and ecological issues. Born in 1944, Salgado began his career in photography in the 1970s.

In his earlier works, Salgados primarily documented social injustice. After engaging closely with human suffering, Salgado subsequently turned to a nature-oriented approach. He remains true to his characteristic style – the intense use of black and white and dramatic contrasts – but with a stronger focus on the preservation and beauty of the earth.

Salgado has been almost everywhere in the world. In Brazil he has photographed in the gold mines of Serra Pelada, and he has travelled to the Amazon region over 80 times. In Rwanda and the Congo he documented the genocide and the displacement resulting from it. In the 1990s he captured the suffering in the Yugoslavian war in his pictures. He also travelled to Antarctica and the Arctic for his book of nature photographs Genesis.

One of his most famous works is from his series Workers (1993), in which he portrays workers all over the world. One particularly well-known image shows miners in the Serra Pelada gold mines in Brazil working like ants in a massive open-cast mine.

It all started with depression. “I had seen such terrible things in Rwanda that I was ashamed to be part of the human race,” recalls Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado in a documentary made by broadcaster Rede Globo. Falling ill both physically and mentally, he retreated to the farm where he grew up, which he was to take over from his parents. Instead of the rainforest he expected, he found a barren, diseased landscape. Would it be possible to sow grass there and breed cattle like his father had done? Salgado’s wife Lélia had a different idea: “We have to replant the forest that was here before.” Salgado registered more than 600 hectares of the site as a private nature reserve and founded the non-governmental organisation Instituto Terra in 1998 to manage it. Since 2023, support for the organisation has come from Germany, via the development and investment bank Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW).

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formIt was not easy at the beginning. 60 percent of the first seedlings died. There was a lack of nutrients and rainfall, and the soil was depleted. As the years passed, Salgado and his team learned to take better care of the young trees. 26 years later, the hills on Bulcão farm in Aimorés have been reforested and additional projects are being developed. “Most of the neighbours had no drinking water on their land,” says Salgado. Their springs were not protected from the sun or from the hooves of the cattle. Instituto Terra had revegetated more than 2,000 dry springs before the first ones start to bubble up again. “Life returned – insects, birds, the first mammals – and as nature began to thrive on the farm, my will to live returned, too,” says Salgado.

Environmental education is another part of the Institute’s work. “I was so excited when I was selected for the Terrinhas project that I didn’t sleep a wink for nights on end,” recalls Thais Moraes Reis. She travelled to the Bulcão farm once a month with a group of other school students from the surrounding countryside who were aged 11 to 12 at the time. “We watched films about the water cycle and about recycling and waste separation.” She spent three years learning with the other Terrinhas, as the children are called. During this time she initiated a waste separation project at her school and planted a vegetable patch with her classmates. Having gone on to do a degree in education, she has now been running the youth projects Terrinhas and Terra Doce herself since 2023.

The work of the institute depends entirely on donations: these are used to finance the 30 employees and the infrastructure, including a tree nursery, off-road vehicles and work equipment. The work with the Terrinhas lay dormant for years for financial reasons. Since 2023, Germany has been the most important supporter of the project through the KfW. KfW portfolio manager Hans Christian Schmidt is impressed with the institute’s commitment, networking and reputation in the region. With 13 million euros in funding from the KfW, the project includes replanting of an additional 2,200 hectares of forest vegetation and the reactivation of more than 2,000 springs and watercourses. The plan is also to implement training and advisory programmes for the dissemination of technologies for reforestation, protection and sustainable use, explains Schmidt.

The aim: to get 360,000 springs flowing again

They used to persuade each farmer individually of the benefits of spring rehabilitation, says Gilson Oliveira, project manager at Instituto Terra and a farmer himself. But now they go directly to the rural cooperatives and associations. As he proudly reports: “We’ve already exceeded our interim target for the current year in June, namely pledges for 427 hectares of reforestation area.” Of course it’s difficult to convince small farmers to designate protected areas that they will lose for production purposes. In the long term, this would only work if they were to receive compensation payments. So the next step is to introduce agroforestry areas which improve the water regime and generate additional yield.

Reforesting the entire basin of the Rio Doce and rehabilitating its 360,000 springs – that’s the dream of Sebastião Salgado and his wife. And that is quite a challenge: with a surface area of 90,000 square kilometres, the basin is as large as the whole of Portugal. “We will manage part of this task with the support of the KfW,” says the 80-year-old Salgado, who overcame his depression and has since produced large-scale nature photographic documentaries. “In this day and age we simply have to plant trees and cultivate species diversity if we are to live in peace in the world.”